Welcome to Spring

The bees have overwintered well and are starting to fly on warm days.

on our Amish friend Moses’ land last week.

We have spent much of the winter making Apitherapy honey elderberry extract and Honey house propolis salve.

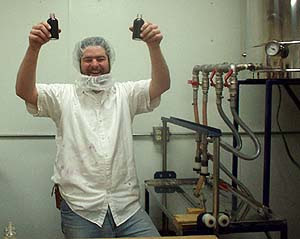

2 bottles of elderberry extract.

As I was walking away from a gathering recently, and someone asked me about the bees.

Wherever I go in northern Vermont, there is awareness and interest in honey bees. People are conscious of the bees and want to know how they are wintering, how the crop is going, or how they are surviving the attack of the parasitic mites.

As I started talking about the bees and how we are now combining honey with elderberry, a group of elder ladies gathered around around and started telling stories about what their parents did with elderberry when they were children. Jam was made, to be used through the winter when someone had a cold or flu, pie and wine were part of the yearly rhythm of the farm kitchen. The ladies were excited to remember a fruit that was important to the family in their youth and that they have not seen much of since then. The elderberry has skipped a generation.

Days after making elderberry, I am still find purple splotches on my clothing. It is a very tenacious berry. At the Vermont Food Venture Center in Fairfax, where we make the elderberry extract,we learned that elderberry is the only food product that stains the white coats we wear there that will not come clean in the wash. This reminded me of propolis that lingers in our bee suits after many washings.

It is now five months since these elderberries were harvested and 12 years since Lewis Hill told me about the elderberries and and encouraged me to get involved with them. The journey has been a long one I reflected on all of this last week at the end of one of Tim and my 11 hour days in the Venture Center making elderberry extract. Purple jars with different formulations were scattered all over the room and we were closing in on the fine tuning for the formula. We were on the edge of finding a way to keep our bees’ Apitherapy raw honey from crystallizing and the elderberry from jellying up in the bottle and still keep the honey totally raw. Samples were delivered by messenger (me) up to a $7,000 computer analyzing each test batch as we tweaked the recipe.

“Tim, we have made elderberry-honey extract !” I proclaimed, feeling almost drunk in the spirit as I realized how we were at the conclusion of many years of work.

“We are not making elderberry, “ he wisely responded, “we are delivering elderberry.”

Thank you for your support of our bees and their work.

The elderberry has long been used for healing in Native America and in the Vermont farm kitchen. Traditionally used for colds and the flu, it is rich in Vitamin C. Elderberry has been known to build up the immunity system and to fight some viruses that chemical medicines do not work on. At the honey house we mix organic elderberry with Apitherapy raw honey, propolis, and organic Echinacea. Propolis is a natural antibiotic gathered by the bees from the buds of poplar and pine trees.

Your food shall be your medicine and your medicine shall be your food. Hipprocrates (460 – 377 B.C.)