a field report from Keith Morris, part 1 of 2

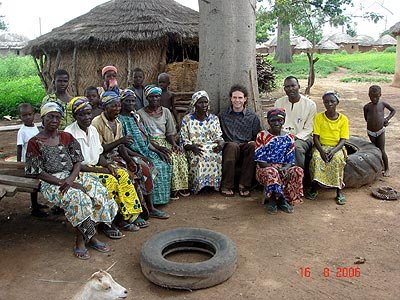

Throughout this past summer I’ve had the honor of working in West Africa as a volunteer apiculture specialist with FarmServe Africa. I met with small family farmers, youth groups, a variety of co-ops, women’s collectives, ‘resettlement communities’, university students and professors, as well as agricultural specialists and extension agents in Nigeria and Ghana, all excited about the power of the honeybee and its medicines.

The art of beekeeping is anything but new to Africa, the original home of the honeybee. As long as people and these creatures have coexisted, there have been ‘honey hunters’, and legends and rituals surrounding this magical insect. The world’s first master beekeepers were the Egyptians, who saw honey as tears of the sun god Ra, and moved hives up and down the Nile on rafts to pollinate crops. Kings and queens were prepared for the journey to the afterlife with giant pots of raw honey, and their bodies were mummified with secret recipes made with the antibiotic and preservative properties of propolis.

In Africa today, the legacies of missionaries and colonialism as well as contemporary corruption and destructive economic development continue to erode agricultural traditions, especially traditions of healing with plants and products of the beehive. The intention of apicultural training programs are primarily economic: to create additional income to alleviate poverty, and to diversify and add value to farms’ products; but the benefits of a partnership between people and these insects are far greater in scope.

The vast majority of people in Africa have little or no access to formalized healthcare, yet are still subject to a dominant cultural perspective that their traditional means of healing are ‘primitive’ and ‘backward’. This has resulted in a tremendous loss of knowledge about medicinal plants and their uses, and a perceived dependence on manufactured ‘medicines’. As I came to realize the magnitude of this loss, I was overwhelmed with gratitude for my community of growers and herbalists at home, and appreciated further the importance of the mission of Honey Gardens. I found new esteem for those who are working to preserve traditions and learn more about healing plants, and these people became some of my greatest allies and teachers in Ghana and Nigeria.

Honey, beeswax, and propolis extracts are ideal mediums for many of the vast diversity of medicinal plants in West Africa; they preserve them and make them more palatable, protect and disinfect wounds, and offer their own important healing and nutritive benefits.

By bringing the beehive directly into the agricultural landscape, we bring in one of nature’s greatest teachers about cooperation and mutually beneficial relationships; the makers of the world’s only imperishable food; greater pollination for crops and higher germination rates in saved seeds; wax for light, preserving wood, batik, and healing salves; the potent and diverse nutrients of pollen and larvae; and the powerful medicine of propolis. These things not only offer potential for an endless variety of products to be made for sale, but most importantly, provide people the increased ability to generate medicines and healing practices for their own communities.

“If we do not do the impossible, we shall be faced with the unthinkable.” Murray Bookchin (1921-2006)